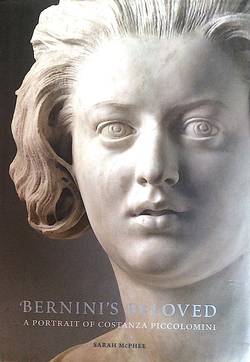

Costanza had been rescued “e faucibus daemonis ” - “from the Devil’s jaws,” as the saying went. Her father, an impecunious footman, left Costanza undowered and thus among those young women thought to be “at acute risk for prostitution.” Between the ages of 14 and 16, she was granted stipends from two religious confraternities, the conditions for which were local residence and rectitude. While her line retained the nominal advantages of nobility, its material trappings were gone. “Bernini’s Beloved,” Sarah McPhee’s scrupulous biography of the statue’s sitter, more often exhibits the latter.Ĭostanza was born around 1614 into the Piccolomini clan, whose prominent forebears included Pope Pius II. A decade before shocking Paris with “Les Fleurs du Mal,” Charles Baudelaire enlivened his 1846 Salon review with the brisk polemic “Why Sculpture Is Boring.” In closing, he weighed the merits of contemporary but now forgotten portraitists, lauding one for “boldness” and “facility of modeling,” chiding the other for “meticulous sincerity” and “dryness.” Giovanni Lorenzo Bernini’s striking “Portrait of Costanza Piccolomini,” carved two centuries earlier, exemplifies the former qualities. The early modernists didn’t look favorably on bust portraiture.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)